When we lived in Jandowae, on the northern Darling Downs, our clothesline was held up with a notched wooden prop.

Previously, we’d lived in houses with that backyard icon of the time, a Hills Hoist. It was efficient. The height could be adjusted, it rotated and it had lots of hanging space.

The Jandowae clothesline, perhaps ten metres long, was height adjustable too, in that you could stand the long prop up at an angle. It was unpredictable, though. A sudden wind gust could fling the drying sheets across to the other side of the line or drop them in the dirt.

A sudden gust will just send a rotary clothesline into a fast spin. Sheets and towels will flap wildly, but they won’t fall in the dirt.

21st century Queensland backyards rarely have space for a Hills Hoist, or a prop line either, even though clothesline props are still being sold, in improved styles. The travelling clothes prop man is a thing of the distant past, and even rotating clothesline are becoming objects of nostalgia. Throughout the suburbs, and across the sprawling, grey roofed, close packed housing developments that surround so many country towns, there is scarcely room for plants.

Last Christmas, Con wrote his Christmas letter on a theme, as he does every year. This year the theme was “clotheslines”. He was searching for a subject more interesting than the usual screeds on family, travel, illnesses and renovations.

Replies to his letter were rich with humour and nostalgia.

One old friend has recently lost his wife of many years. He misses her. But there is a positive side, as he wrote, and it concerns how he hangs out the washing now she’s gone.

- No more separate washing for whites and colours.

- No more hanging tops from the bottom and bottoms from the top.

- No more delicates.

- No more taking pegs off the line and into the peg basket.

- No more socks by the toes. No more pockets turned out.

Surely one of the small freedoms we can allow ourselves is to hang out the washing any way we like. Leave the pegs on the line, or put them in the basket? Hang the socks in pairs, or randomly? Wooden pegs or plastic? One peg, or two? Please yourself.

From my verandah I can look across the next-door backyards with their rotary clotheslines and I notice how they hang out their washing. The young couple next door hangs clothes entirely randomly, and not always using pegs. Next yard across, the retired couple hangs theirs out according to a strict pattern. Six white knickers in a row, six black underpants, six singlets.

It seems they shop for underwear in an orderly way too.

Our friend in Chicago responded to Con’s letter wistfully. In the depths of winter and living in an apartment, she has no chance of drying her washing in a sunny, breezy garden.

Queensland climate varies dramatically across its huge area. When we lived in Burketown and Townsville, I had no problem drying the clothes either outdoors, or if it was raining, on lines strung under the house. However, Townsville, as they say, is a “dry old hole” most of the time; and Burketown is almost desert for a lot of the year. In Burketown, I would hang my washing under the house in the cool of the evening, and next morning everything would be dry.

Things changed when we moved to Yarrabah, on the coast near Cairns, with a ten-day old baby, and pouring rain and a cyclone predicted. Faced with the thought of managing wet cloth nappies, Con came home from the local store with a tumble drier.

Con enjoys doing the washing. He has hung out clothes in Gulf Country heat at Karumba;

at the back of the old shearers’ quarters on Carisbrooke Station, west of Winton;

on the elevated clothesline behind a Silkwood farmhouse in Far North Queensland.

It’s a unique feature of elevated FNQ houses, a relic from the 1950s and ‘60s: a Hills Hoist mounted on the end of a concrete walkway leading from the back door.

Otherwise, hanging out washing in a wet, tropical climate is not easy. Taking advantage of the first good drying day following a week of downpour, you stand in rubber thongs in the mud, flinging towels and sheets across the line, hoping nothing drops or drags on the ground.

One North Queensland wet season we stayed with Con’s brother and sister-in-law at Balgal Beach, north of Townsville, for their wedding anniversary party.

On the party tables, Margaret had used all her beautiful old tablecloths. Next morning we washed them. The grass was still soaked from a downpour, and it was tricky, hanging out those gorgeous old cloths without trailing them in the wet grass and mud.

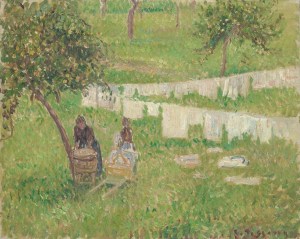

Washing moving in the breeze can be beautiful. It’s the fresh air and sunshine, the colours, patterns and fabrics. The sight has inspired many artists.

A feature of Queensland Art Gallery’s collection is “Washing Day at Éragny”, one of French Impressionist Camille Pissarro’s many beautiful paintings of women washing and drying clothes.

Another of QAG’s treasured paintings, “Monday Morning” by local artist Vida Lahey, depicts a traditional washing day, with women scrubbing clothes, bending over the concrete laundry tubs that were once a feature of Queensland laundries and are now seen in the bathrooms of trendy pubs.

Another friend reminded us of the work that went on around those laundry tubs. I can still see my hard-working Mum dragging the boiled sheets out of the copper with the boiler stick, then on to the hand-turned wringer and out on to the propped up washing line, only to sometimes blow down into the mud!

My friend Marion, married to a vet, also responded to Con’s Christmas letter.

For the first time in my life I no longer have a washing line. For years I’ve joked that it was my daily exercise, carrying baskets of washing up and down stairs, bending and stretching to hang the washing in the open air.

My worst washing memories are of cleaning Malcolm’s overalls after he had done a messy calving case out in a muddy paddock somewhere. No washing machine, no hot water in the accommodation we were living in, in the dairy country of the Illawarra. Had to use the bath for a while until we bought a second-hand washing machine. The memory still lingers, particularly the smell of muck and blood. Lovely new calves came into the world though. Clever vet.

The harsh Queensland sun dries towels and sheets fresh and clean. The sun is a great purifier, a killer of germs and mould, although I had an aunt, a meticulous housekeeper, who told me darkly what she thought of this theory as applied to lazy laundry habits: “Some people leave far too much to the sun…”

I had a near-disaster one washing day.

Our cat had gone to sleep among the dirty clothes in the top-loading washing machine. Not noticing, I added powder, closed the lid and started the wash cycle. Seeing some clothes I’d missed I opened the lid again to put them in. The wet and terrified cat jumped out, disappeared out the door and was not seen again for hours.

Main picture: Swell Sculpture Festival, Currumbin Beach, Queensland. 2015