In 1972 we were living at Rosevale, 50 kilometres southwest of the city of Ipswich. We went to Ipswich to shop, but our nearest town was Rosewood. As in all regional areas, sport is strong around Ipswich, and Con played cricket on the Rosewood United team, in an Ipswich competition. One team member that he got to know, named Daryl, was a coal mine rescue worker. Daryl’s father was a miner, too.

At 2.47 a.m. on 31 July 1972, a mining disaster occurred in the Box Flat coal mine, a few kilometres southeast of the city. When a huge explosion occurred, seventeen miners and rescue workers were killed, with another dying later of his injuries. Daryl was one of the men killed; and so was his father.

No one underground at the time could have survived; the bodies could not be retrieved, and the difficult decision was made to permanently seal the mine.

The whole region grieved. Mining communities are close-knit, and it was said that everyone in the district knew someone who died that night.

A video from the Mine Safety institute of Australia covers the story of the disaster. https://youtu.be/m-dXzS5KanI

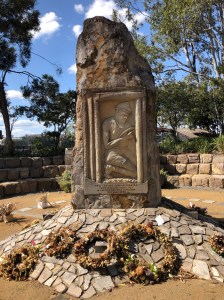

The sombre Box Flat Memorial was constructed at Swanbank, near the scene of the disaster.

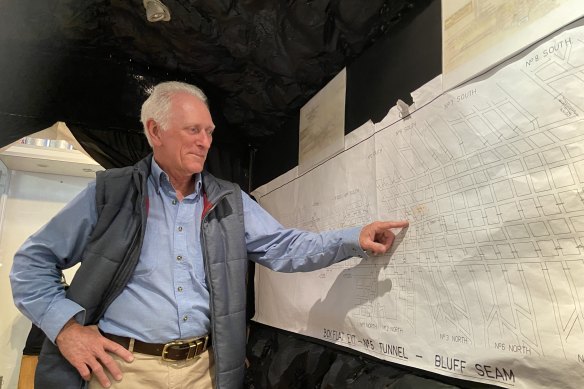

Last week I visited the Memorial, then drove to the site of the Cooneana Heritage Centre a few kilometres away for more information. This is the home of Ipswich Historical Society and of the original Cooneana Homestead, built in 1868 and lovingly preserved.

The Society’s headquarters and museum are housed in an attractive, award-winning Modernist building, constructed in 1976 as the offices of Rhondda Collieries and still in its original condition.[1]

Coal is why ipswich is where it is. Coal and limestone.

In the early, convict days of Brisbane when building was progressing, lime was needed for mortar. In 1827, Commandant Patrick Logan, energetic explorer of the Moreton Bay area, discovered limestone deposits on a hill above the Bremer River in what is now Ipswich. A small convict outpost called the Limestone Station was set up, with George Thorn as overseer, and lime burning kilns were constructed.

Cunningham’s Knoll on Limestone Hill is a spectacular pyramid of limestone terraces built in the 1930s as a Great Depression employment project. On top of the Knoll, old fig trees grasp blocks of raw limestone in their buttress roots.

Little remains of the old kilns now except for a small mound of kiln residue behind the Knoll.

Patrick Logan also discovered coal reserves near Limestone Hill, and over time coal mines were opened all around the area, with miners coming from as far away as Wales. The suburb of Blackstone is still known locally as Welsh Town, and Rhondda Colliery and the suburb of Ebbw Vale were named after coal mining areas in Wales.

My own connections with Ipswich go back to 1861, when my great-great-grandfather James Matthews, fresh from England, spent a night there, enjoying the hospitality of the same George Thorn, probably in his hotel, the Queen’s Arms (soon to be re-named the Clarendon), on the corner of Brisbane and East Streets: Ipswich’s first licensed hotel.

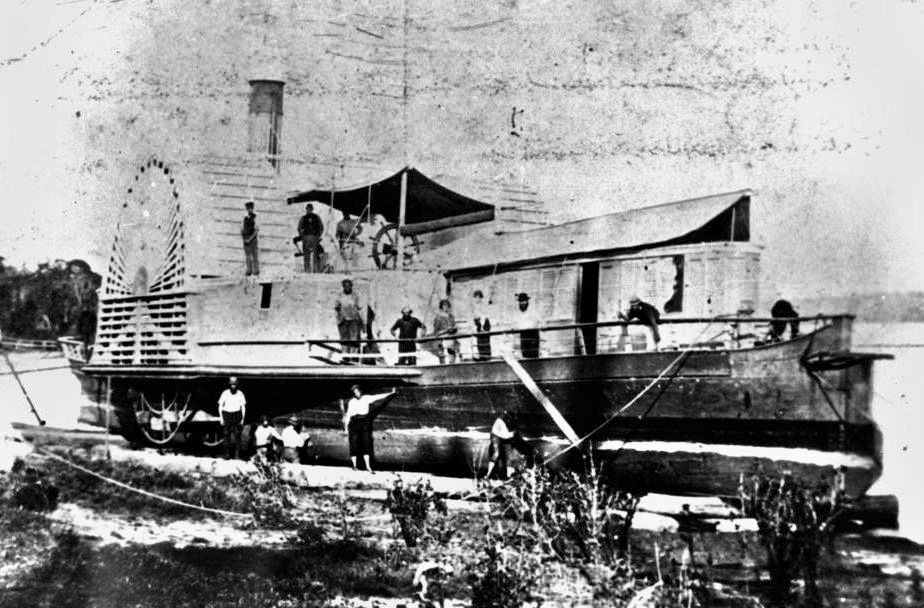

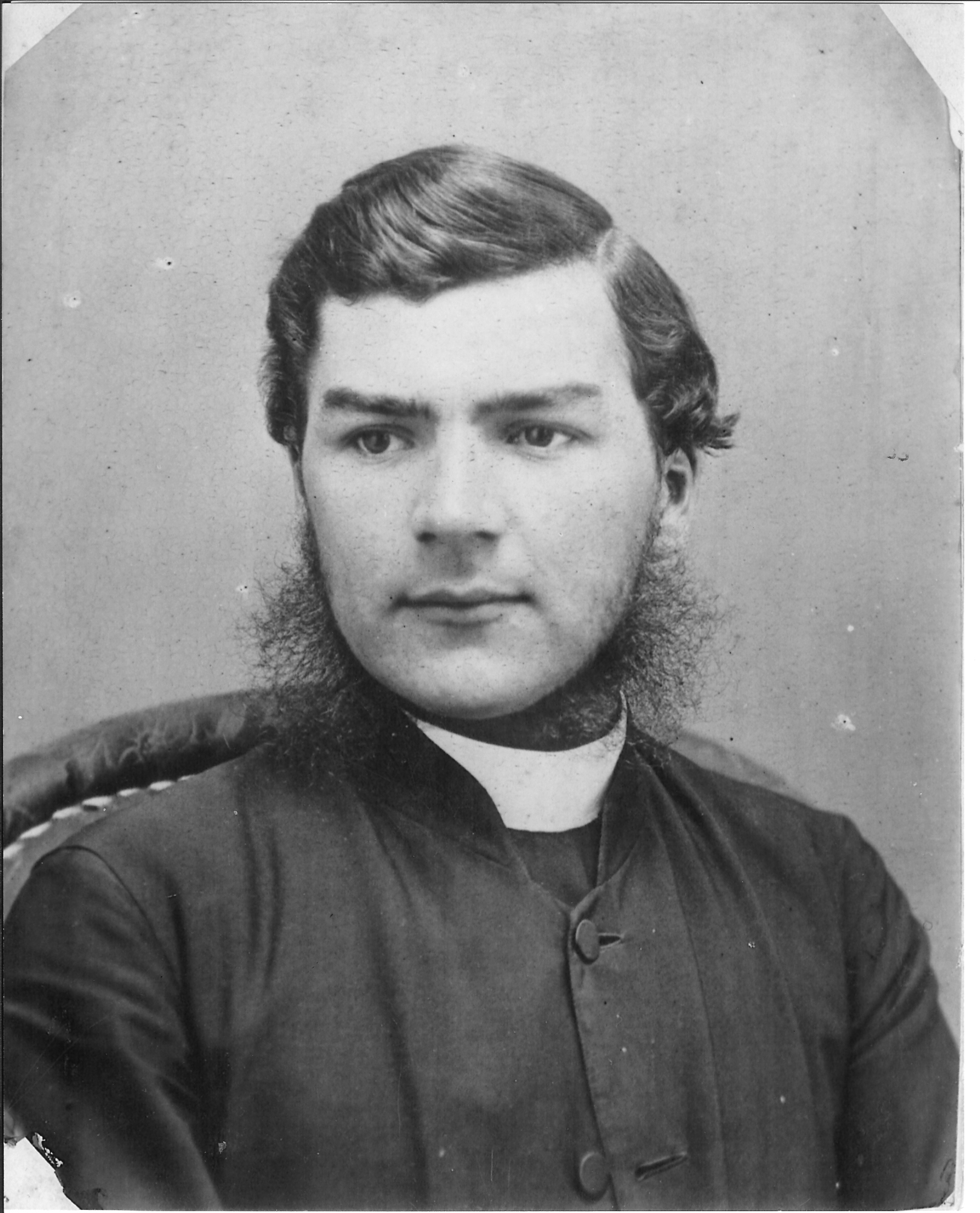

James had come up the Bremer River by paddle steamer, with Archdeacon Benjamin Glennie, and the next morning they set off together to walk to Warwick. (See my story “Walking to Warwick” https://roseobrienwriter.blog/2018/07/27/walking-to-warwick/ )

George Thorn, like many colonial officials, businessmen and squatters, was an English ex-military man who did well out of being in the right place at the right time. He became a major landholder and a Parliamentarian, influential in the colony of Queensland, and regarded as the Father of Ipswich. “Claremont”, the house George Thorn bought at the river end of what is now Milford Street, is sometimes opened to the public for the Great Houses of Ipswich weekend. “Claremont” is just one example of Ipswich’s many magnificent old homes and its fine civic buildings.

Ipswich became a steam railway centre, and in 1865 the first railway line in Queensland was opened, running to Bigge’s Camp/Grandchester, about thirty-four kilometres away; the first stage of a line to Toowoomba. The railway workshop established in North Ipswich, now home of the Workshops Railway Museum, became the state’s biggest employer, constructing over 200 steam locomotives in its time.

In the 1850s, as statehood for Queensland approached, there was an unsuccessful movement for Ipswich to be chosen as the new state Capital. The owners of the Ipswich paper, The Queensland Times, pushed for it. This fine old masthead continues today. However, once News Corp bought it, its print days were numbered, like so many of Queensland’s regional newspapers; and now The Queensland Times is only available online.

Losing a local print newspaper is a bad thing for communities. Local news is no longer covered in detail; and people without online access might not find out until a year after the funeral that someone they knew has died.

In the early 1980s, Con and I returned to the area, to the farming town of Lowood, 35 kms to the northwest. Again, Ipswich was our shopping town, and again I shopped at the iconic old department store of Cribb & Foote, then Reid’s, on Brisbane Street, just a block up the street from the site of George Thorn’s hotel.

Thorn’s hotel had eventually been destroyed by fire. Shockingly, in 1985 Cribb & Foote also burned down, leaving a massive gap in the CBD.

Ipswich is to Brisbane as Newcastle is to Sydney, or Geelong is to Melbourne: the tough industrial neighbour with a slightly grimy reputation. Each of these old cities has had to reinvent itself as local industry changed. The Ford car factory in Geelong has been closed for years. Newcastle no longer builds ships; and the last coal mine in Ipswich closed in 2019. In each case, the city has moved to meet the challenges.

New communities have grown up in the ex-mining and scrubland country of the western growth corridor between Brisbane and Ipswich. Ripley, with ambitions to become Australia’s largest planned community, is currently under development only a couple of kilometres from Swanbank, the site of the Box Flat disaster.

Highways are expanding to meet the challenge of increasing population, and busways and extensions of the railway network are under consideration.

In 2013, an initiative to reverse some of the peak hour commuter traffic on the Ipswich Motorway to Brisbane and revitalise the CBD was completed. On the site where Cribb and Foote once stood, the Icon Tower was constructed, an office building occupied almost entirely by Queensland State Government departments, including, appropriately, the Department of Resources.

We live in Brisbane now, but we often take our grandchildren to the playground and Nature Centre in Queen’s Park, on the slopes of Limestone Hill; we visit Nerima Japanese Gardens, and the Ipswich Art Gallery, with its wall of coal. We visit cafes and the river walkways, restored after recent Bremer River floods. It’s a quiet river when we visit, and it’s hard to imagine the devastation it regularly causes through the low-lying areas of the city.

This is not soft country. The Ipswich area is hotter in summer and colder in winter than Brisbane. Living at Lowood, we sometimes scraped frost off the car windscreen at eight in the morning. At Rosevale in 1972, we suffered the hottest Christmas of our lives, with all-time record temperatures.

For the sad coal-mining families in the area, there would have been empty places at the table that Christmas.

[1] Thank you to Ipswich Historical Society President Hugh Taylor and other well-informed staff who generously helped with information and access to files when we visited Cooneana Heritage Centre.