“Why don’t we have a beach house?” Lizzie wants to know. “Our families used to have beach houses. Currumbin, Maroochydore, Alexandra Headland, Yeppoon. Where did they all go?”

That happens with real estate. Life changes and financial situations get in the way.

“If only they’d held on to that house/that piece of land – it would be worth millions now,” we say.

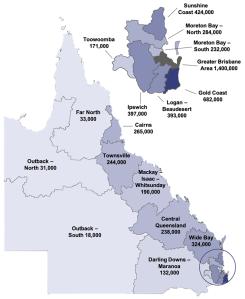

Queensland has 13,347 kms of coastline, including its 1,955 islands, and 715 recorded beaches. (ozbeaches.com.au)

Over 70% of the population lives within twenty kilometres of the coast.

We go to the beach a lot.

This said, much of the coastline is lined with mangroves and mud, isolated, and infested with crocodiles and stingers, and because it is sheltered by the Great Barrier Reef and the islands has no surf. Great for fishing; not so great for swimming.

These days, owning a house near any actual sandy surf beach along the Queensland coast, from Yeppoon to the New South Wales border, is for the wealthy.

Last century, development along the coast was nothing like it is today. My mother’s father, Fred, was manager of a sheep station outside Barcaldine, 620 kms to the west, and he bought a house at Yeppoon. According to my aunt, who remembered it from her early childhood, it was a traditional timber house on the side of the hill, looking out over the sea, with a steep path down to the beach.

Like many Central Western Queenslanders, my mother’s family regularly holidayed at Yeppoon and nearby Emu Park. They took the train from Barcaldine, changing trains at Rockhampton and continuing down to the coast. Today, the railway line to Yeppoon has gone.

Now Yeppoon is a modern beach resort town, with spectacular houses and apartments listed on Airbnb; many of them, no doubt, occupied still by holiday makers from the Central West. Fred’s old family house would have been demolished years ago.

Fred and Phyl ended their lives back at the seaside, with a house on the hill at Currumbin Beach: a nice house with a three-bedroom flat under it for visiting family, and a fine view down to the sea and Elephant Rock, where we used to play and climb.

When Fred and Phyl died, the house was sold and demolished. Townhouses were built on the block.

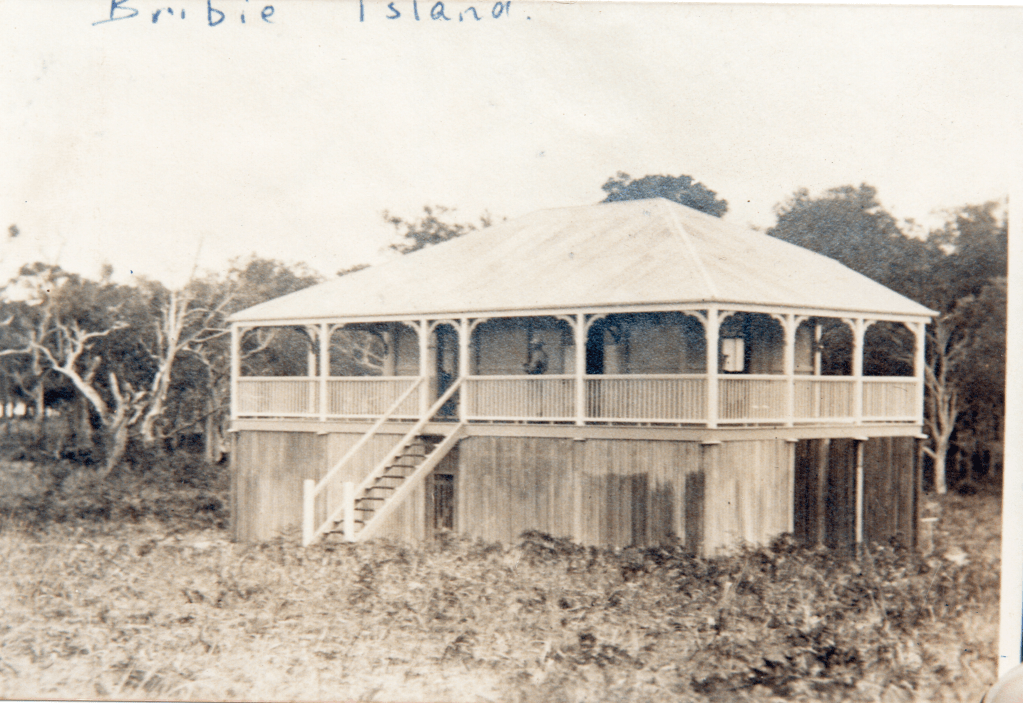

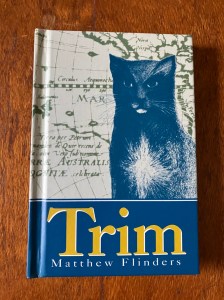

Our earliest family beach house was built in the early 1900s, at Bribie Island, on the Pumicestone Passage side (now known as Bongaree), not far from where John Oxley had moored his small ship just eighty years earlier, and Matthew Flinders before him. The family would travel there on the excursion boat “Koopa”.

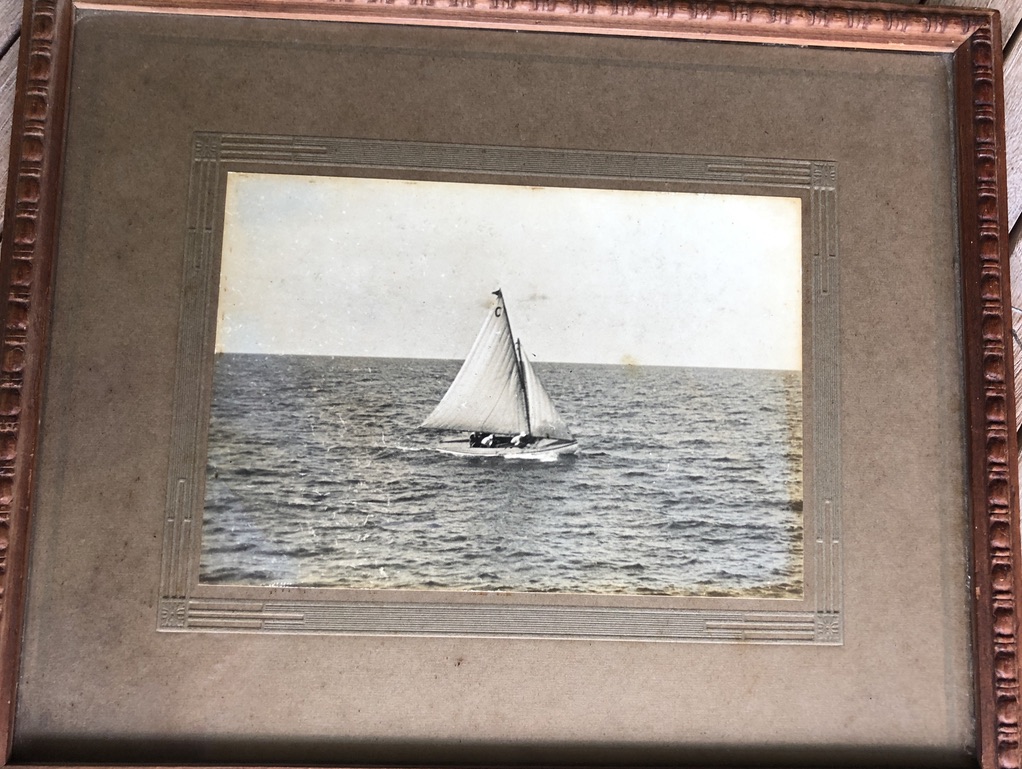

The house was built by my father’s grandparents, who loved boats and the seaside, and spent time sailing on Moreton Bay.

The old man, my great-grandfather, was descended from a ship’s pilot from Kent.

These things go down the generations. Maybe that’s where Lizzie’s love of the water comes from.

My father’s parents had a north-facing house on Alexandra Headland from the 1920s or earlier, when the Headland was almost bare of buildings but covered in coastal scrub.

The Alexandra Headland house, known to the family as the Coast House, had timber shutters propped out by struts instead of windows, a dunny out the back and a cold shower under the tank stand, and a view along the beaches as far as Noosa Heads. I remember lying in bed in the little verandah room, with a row of shells on the windowsill and the sound of waves crashing on the rocks below. Lizzie would have loved it.

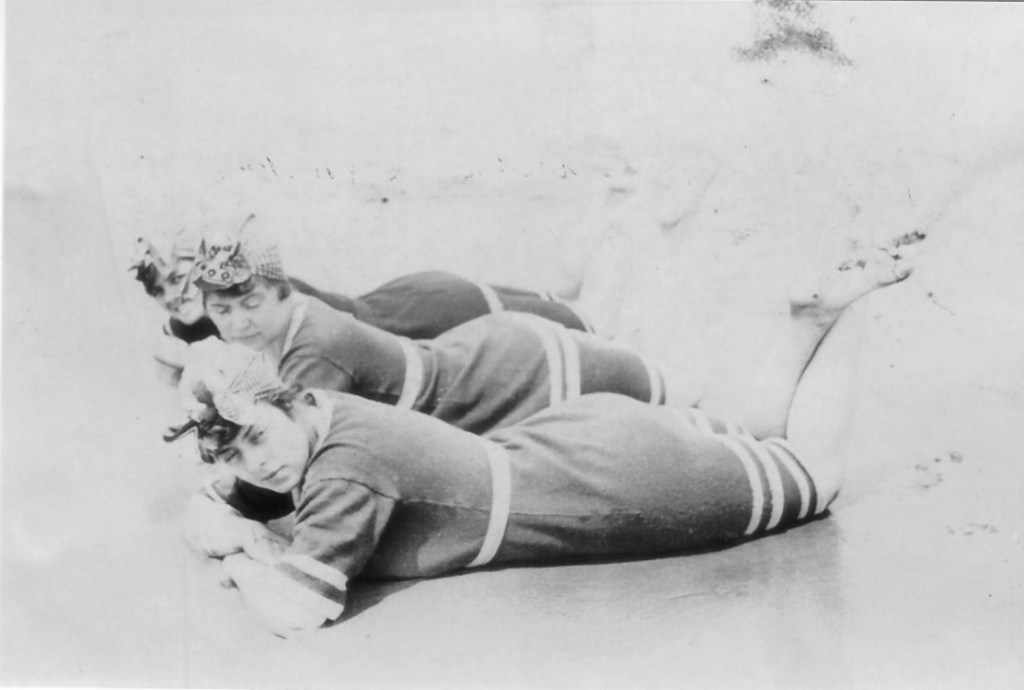

As a teenager my father was a member of the Alexandra Headland Surf Club, even leading the club team at surf carnivals. Many family get-togethers happened on that beach, up until my grandmother died in the 1970s and the house was sold. An ugly brick apartment block occupies the site now.

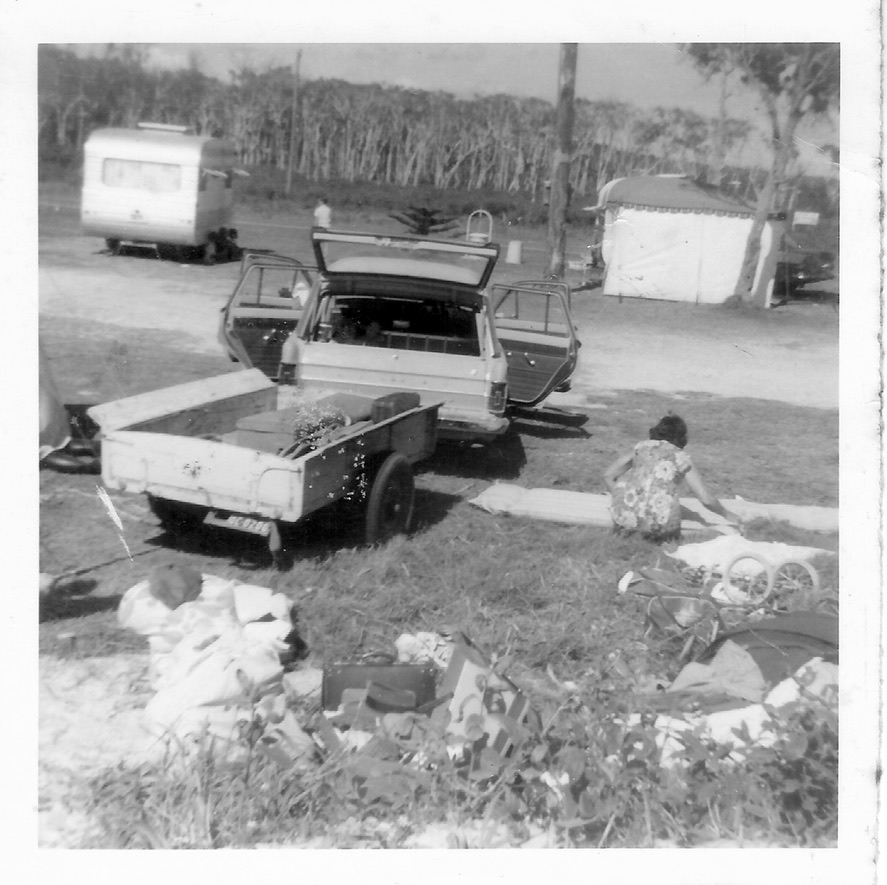

We still visited Alex for our holidays though, camping in the Caravan Park.

In the 1950s my parents bought an old timber house on a dirt road running along the Maroochy River. It had two bedrooms and a sleepout, an enclosed verandah, and a kitchen with an ice chest. Dad concreted under the house and installed a cold shower down there. The dunny in the back yard was sheltered from view by an enormous purple bougainvillea, and there were possums in the ceiling. We called that house Toad Hall, and we loved it.

We swam in the river, jumped off the jetty, and went sailing in our new boat.

After working all week, my father would complain about having to spend half of Saturday mowing the lawn at Toad Hall. That’s the downside of owning a beach house: the maintenance.

Toad Hall was sold when we moved to Brisbane and it survived for many years on Bradman Avenue before progress came along and the house was demolished. Apartments were built on the site.

One Christmas I went searching for a family holiday house to rent, on the coast, in the southeast corner, and I had to go as far north as Agnes Water before I could find one that would fit us all. It was a couple of blocks back from the beach, with “ocean glimpses” from its verandah.

In the resort towns on the Sunshine and Gold Coasts, there are fewer waterside holiday houses now. It’s nearly all apartments.

Where would Lizzie have to go, to buy a beach house with ocean or water views?

And what would it cost?