In late September I take a two-hour flight from Brisbane to Charleville to meet my son Joe and his family.

Rex Airlines is subsidised by the government for regional flights like this. In a two-prop Saab 340 with seats for about 30, with only a dozen or so passengers, I fly west over the ranges. Smoke from bush fires rises from the forests below.

We’re told we can pick up our checked luggage from the carousel in the terminal. There is no carousel in the tiny Charleville Terminal. The bags are lined up on the floor.

I remember the Burketown airport, years ago, where a small tractor drew up outside the terminal and we grabbed our bags off its trailer at random. Joe tells me of a regional flight in Russia when their bags were tipped out unceremoniously in a pile in the snow.

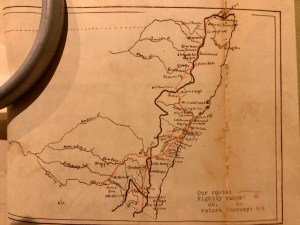

Outside the terminal I’m greeted by Danny and Pete, aged 11 and 9. With Joe and Isabel they’ve driven 1,325 kms from their home at Babinda, south of Cairns; equivalent to driving from London to Edinburgh and back, but with less traffic. And fewer people.

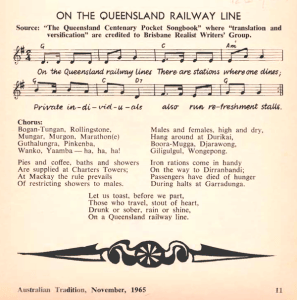

They’ve spent nights at Charters Towers (pop. 8,040 in the 2021 census according to Wikipedia) and Blackall (pop. 1,365), with stops at Torrens Creek (pop. 46), Barcaldine (pop. 1,540) and Augathella (pop. 328).

This school holiday weekend, the Mulga Cup is being held in Charleville. Two hundred under 11 rugby league players in twenty-two teams, from as far away as the Gold Coast, are in town, with their families. Accommodation is hard to find.

In western Queensland, towns are far apart. We can either backtrack to Augathella, 84kms to the north, where there is one room available in the motel behind the pub, or head out to Quilpie, 211kms; but the whole of Quilpie (pop. 530) is booked out because there’s a wedding in town this weekend.

Before leaving Brisbane, I’d rung my list of Charleville motels again, and found a lucky cancellation. We get to stay here and see the Bilby Experience, look at the stars and planets at the Cosmos Centre, and visit the Royal Flying Doctor Service Visitors Centre.

At the Visitors’ Centre I give Pete a fifty dollar note to post in the donations box. He looks at me in surprise, but I’m remembering the two Flying Doctors emergency flights I’d had out of Burketown, years before. The RFDS is vital in the bush.

Then we’re off to the west.

90 kms out on the Diamantina Developmental Road to Quilpie, we stop at the iconic Foxtrap Roadhouse. This is a place with many stories to tell.

While we’re there, a man and a woman in work clothes come in and settle on stools near us. They’re from the cattle station across the road, and they smell like hard work and horses.

“I’ve been mustering and branding all morning”, the woman tells us. We have an interesting conversation. As a tourist it’s not often that you get to really talk to locals. It turns out that this little roadhouse, seemingly isolated, is the centre of a local community of station people and workers, and not lonely at all.

Much of western life is invisible in the towns. It lies down those unsealed side roads, marked sometimes by a sign, a mailbox and a cattle grid, that lead to the homesteads and outbuildings of cattle stations; or the roads leading to mines or gas fields.

People from the stations go to town only occasionally – for council meetings, the pub, the rodeo or the races, the doctor, or the school if they’re on a school bus route.

From Quilpie we turn south on the road to Thargomindah (pop. 220), with white and yellow wildflowers carpeting the verges and spreading across the paddocks in every direction. It’s springtime, and this country has had more rain than usual.

In the Thargomindah Explorers Caravan Park we stay in comfortable units built high enough to have avoided the flood that almost wiped out the town in mid-April 2025. Much of the Park looks as if the rushing water swept it bare.

What the locals call Thargo is on the banks of the Bulloo River, and it was the Bulloo that did the damage. According to news reports, every business in Thargo and 90% of homes were inundated. Most of the population was air-lifted out of town, with some staying on higher ground at the airport in cars and campervans until the water went down.

Isabel visits the town swimming pool with the boys, but it’s closed, being cleaned for the third time to get rid of lingering mud.

Instead, we walk down to the river, and she and the boys go swimming in that milk coffee coloured water. For children who’ve grown up in the pristine creeks of Far North Queensland, swimming in water you can’t see through is something new. At least out here in the west they don’t have to worry about crocodiles.

There are new houses and functioning businesses in town, and a sign-posted Heritage Trail, but to the boys, swimming in the river is the only interesting thing about Thargomindah.

Danny asks me, “Why are we driving all this way to places where there’s nothing to do and nothing to see?”

I try and explain.

“This is home for the people of Thargo. They need visitors like us to come and support their town after the flood. They’re Queenslanders like you, and they’ll be supporting the Broncos tomorrow night, just like you will be!”

The following night, the Brisbane Broncos meet the Penrith Panthers in a National Rugby League preliminary final. As Broncos supporters we must not miss the game.

At Eulo (pop. 94), 67 kms west of Cunnamulla, I book cabins behind the Eulo Queen Hotel.

The pub closes at 4pm on a Sunday, before the match is due to start, but the publican offers to take a television out to the shed. The new owners are from Tasmania, and I don’t know if they appreciate the importance of rugby league to Queenslanders. AFL would be a different matter.

There’s nowhere else in this tiny town to watch the game, except for private houses, so a number of people join us in the shed – the pub cook, a few travellers from the cabins, and a bloke from off the street. A fisherman, one of many heading out to catch yellowbelly in the brimming western rivers, comes along with his young son. It’s an exciting match, and to everyone’s delight the Broncos win.

From Eulo we pass through Cunnamulla (pop. 1233) to St George, a pleasant town (pop. 3130) where we stay in an old house restored as Airbnb accommodation. The boys and Izzie miss their anticipated swim in the Balonne River because there are brown snakes in the muddy water around the pontoon.

After Texas (pop. 790), on the New South Wales border, the road takes us through hilly sheep country to Stanthorpe (pop. 5286), the biggest town on this trip since Charters Towers.

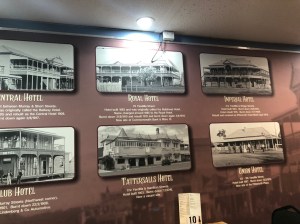

Fine old towns like Barcaldine, Charleville and Cunnamulla were built on the wool industry, but these days it’s cattle across most of the state, and the towns have suffered. Fewer people, less money coming in.

In picturesque granite country, surrounded by orchards and vineyards, with a beautiful national park nearby, and within an easy drive of Brisbane, Stanthorpe has more obvious charm and prosperity that any of the other towns we’ve visited.

Con has come up from Brisbane to meet us, and next day he and I drive home together while the family heads further south.

Joe and his family have driven 2621 kms from Babinda to Stanthorpe, equivalent to driving from London to Prague and back. They’ll need a few days of rest before heading back to Brisbane, then starting the 1645km slog up the coastal Bruce Highway to their home.

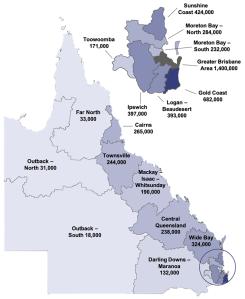

Queensland has an area of over 1,700,00 square kilometres and a population of under six million. According to Queensland Government statistics, only 2% of Queenslanders live in the outback; and in the southern outback region that includes Thargomindah that number is dropping.

Flood, fire and drought can and do hit everywhere in Queensland. It’s just that much harder in the isolated western regions. It’s great that more and more people from coastal Queensland are taking their caravans, campers and kids to see what lies out beyond the coastal ranges.

While they’re there, they should donate to the RFDS.

Main photo: Sunset over the Thargomindah Caravan Park photo: Alexandra Knott