“The settlement,” Cowper had told Clunie on the Isabella, “is mostly on one point of land. Penis-shaped, we shall say, backed by a high ridge we shall call the Line of Bollocks.”[1]

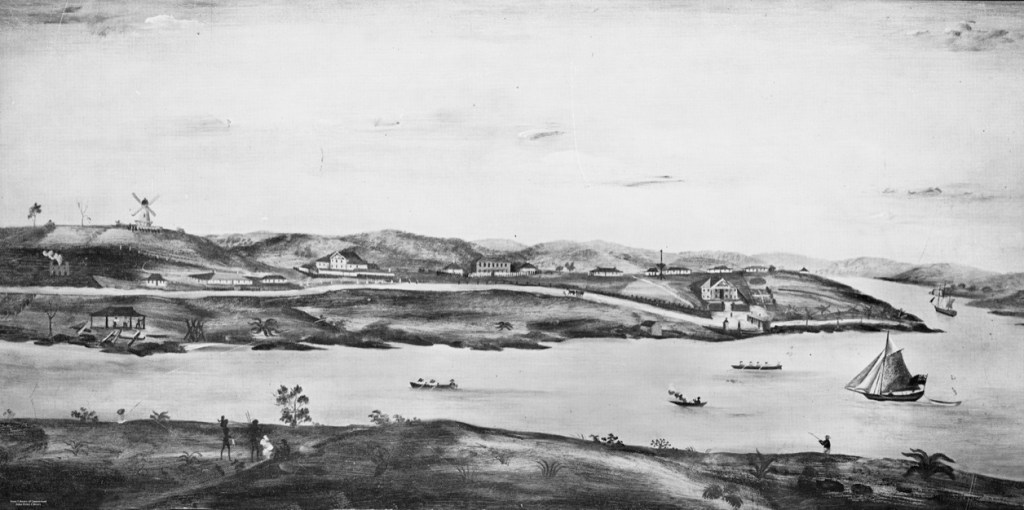

Jessica Anderson wrote a wise and interesting novel of convict Brisbane, “The Commandant”, published in 1975. It includes this pungent description of the site of the Moreton Bay Convict Station, in the words of the notoriously bitter, badly-behaved drunk, Henry Cowper, the convict station’s first medical officer. The site of the Moreton Bay Convict Settlement, established in 1826, runs along the ridge where William and George Streets run now.

Queensland’s government buildings still occupy this “penis-shaped” piece of high ground along the river.

Henry Cowper was the medical officer for the Settlement from 1826 to 1832. He worked in primitive conditions in this isolated, under-funded and under-supplied outpost of the British Empire. Captain Patrick Logan was the commandant.

Jessica Anderson’s excellent novel was thoroughly researched, and conditions in the settlement, and many of the characters, are based on records of the time. The novel culminates in the sombre discovery and retrieval of the body of Captain Logan.

Captain Patrick Logan of the 57th Foot Regiment, a veteran of the Peninsula War against Napoleon, was commandant of the settlement from 1826 until his murder in 1830 at the age of just thirty-nine.

Many men who came to Australia in the early years of European occupation, to supervise convict stations and run governments, were veterans of the European wars of the early nineteenth century. Violence and flogging were not new to them. Logan was a notoriously harsh disciplinarian who followed the rules without mercy. The floggings Logan ordered for convicts would have provided Cowper with a stream of grievously injured patients.

Constant complaints about the treatment of Moreton Bay convicts were made to the government in Sydney. The famous old song “Moreton Bay” has a convict describe it:

For three long years I was beastly treated

And heavy irons on my legs I wore

My back from flogging was lacerated

And oft times painted with my crimson gore

And many a man from downright starvation

Lies mouldering now underneath the clay

And Captain Logan he had us mangled

All at the triangles of Moreton Bay

Like the Egyptians and ancient Hebrews

We were oppressed under Logan’s yoke

Till a native black lying there in ambush

Did deal this tyrant his mortal stroke

My fellow prisoners be exhilarated

That all such monsters such a death may find

And when from bondage we are liberated

Our former sufferings will fade from mind[2]

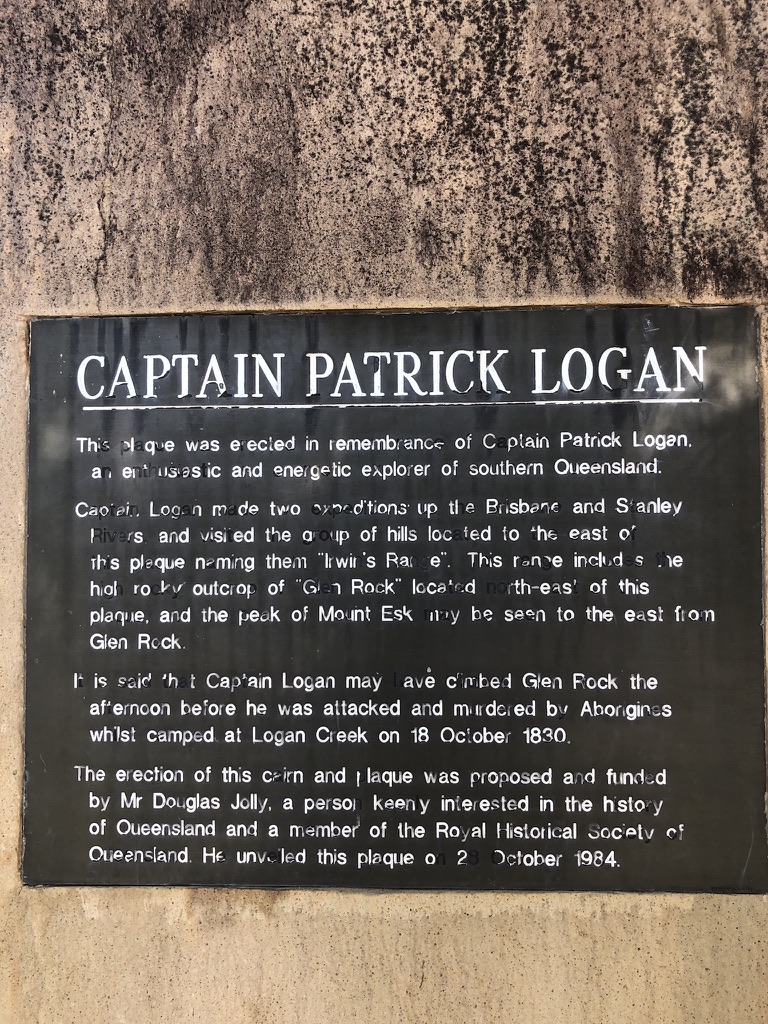

In Esk, in the Brisbane Valley, the Memorial Park has shady trees and picnic tables. We stopped there for lunch one day. Sandwich in hand, I wandered around the park, and found a rock with a plaque attached. The plaque describes Patrick Logan as “an enthusiastic and energetic explorer of Southern Queensland’, and provides the information that it was near here, on 18 October 1830, on his last exploratory trip before his term as commandant was over, that he was killed by an Aboriginal group.

It may be true that escaped convicts were also involved in Logan’s murder; but there is always going to be violence when one group invades another’s traditional homelands and takes them for their own.

Patrick Logan made frequent exploratory expeditions and is credited with many “discoveries” in south-east Queensland. His name is on lookouts at Rathdowney and Mount French in the Scenic Rim. He is credited with discovering the Logan River, Dugulumbah to Yugumbeh people who had known it for thousands of years. Logan Road, the City of Logan, and many other plaques, streets and suburbs carry his name.

During Logan’s time as commandant, the first permanent buildings in what was to become Brisbane were erected. Two of them still stand: the windmill up on Wickham Terrace (on Cowper’s “Line of Bollocks”, in fact) and the Commissariat Store in William Street, the oldest inhabited building in Brisbane. The Commissariat Store building is now the Convict Museum and the headquarters of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, and on its lower floor can be seen models of the Convict Station the way it looked at the time of Logan’s death.

These include a model of the Commandant’s house, with a verandah in front.

A museum volunteer tells me that the house, which features in Jessica Anderson’s novel, looked across William Street to the river, near the site where huge casino and hotel buildings are currently rising: the Queen’s Wharf Development Project.

According to the website, the finished Queen’s Wharf development will include a Sky Deck 100 metres above William Street, and fifty restaurants, bars and cafes.

This whole area is a massive construction site; and in the midst of it sits, incongruously, the Commissariat Store.

I’m told the developers wanted to take over the convict-built Commissariat Store. It would have made a fine site for a restaurant and bar, this old stone building opening out on to the riverbank. But somehow the RHSQ managed to keep it.

Other historical buildings within the William and George Street precinct are being protected and preserved, but it’s difficult now to imagine the environment of simple wooden buildings, dirt pathways and gardens that occupied this stretch of land two hundred years ago.

Today there’s a huge, powerful white snake rearing out of the Brisbane River, looking as if it’s about to strike.

It’s the new Neville Bonner Bridge, startling in its design but destined to become a Brisbane icon. The last sections have been craned into place, and soon pedestrians will be able to cross from Southbank Parklands to take part in the promised glories of the new development.

The ridge above the river will never be the same again. Patrick Logan would not recognise it.

It’s to be hoped that enough well-off tourists come to spend their money there to pay for it all.

[1] “The Commandant”, Jessica Anderson. First published 1975. This edition: The Text Publishing Company, Australia. 2012. P. 74.

[2] folkstream.com