This is a Queensland story that is worth telling again and again.

The Opening Ceremony for the 2024 Olympics took place on 26 July, but the Olympic Torch had already arrived in Paris. I know it had, because my granddaughter sent me a video from Paris ten days earlier of the torch procession travelling down a Parisian boulevard. A tall young man dressed in white is running with the torch held high.

Con was moved by the thought of his granddaughter watching the Olympic Torch making its way through Paris, because as a young boy he’d watched an Olympic Torch being carried through Innisfail, Far North Queensland, by his brother Jim.

To qualify as a torch bearer for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, you had to be able to run a mile in under seven minutes. And you had to be a man. Jim was a good miler, and he carried the torch from the Innisfail Shire Hall, down the hill and south across the river to hand it over to the next runner.

There was a huge crowd in town to watch the torch go through. Then as now, international events didn’t often touch Queensland towns.

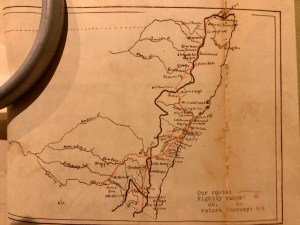

The Torch Relay for the Melbourne Games began in Cairns on the ninth of November when the flame was flown in from Greece. The Relay caused excitement all the down the east coast of Australia. As the Relay passed through small towns and regional cities local people in huge numbers watched its progress.

The most testing sections of the Relay were in Queensland.

Setting up the Relay had been an epic in itself. Nineteen days earlier a convoy of army trucks and Holdens had set out from Melbourne on the road trip to Cairns, loaded with torches, fuel, medals for the runners and other equipment. The convoy was manned by army personnel and Melbourne university students.

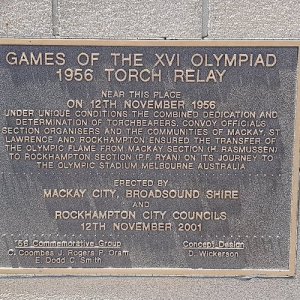

Perhaps the route had been planned using maps, not local knowledge, because heading north from Rockhampton through a stretch of country that was virtually unknown to the southern states, the convoy took the coastal route via the tiny railway town of St Lawrence, following the train line, instead of the Bruce Highway (such as it was), inland through Lotus Creek.

The coastal route was a dreadful track of creek crossings, potholes, swamps and cattle grids.

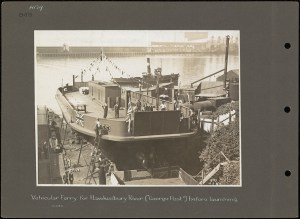

In the end, it was impossible. At St Lawrence the convoy was loaded on to a train to make the journey to Sarina, being bogged down once again before making it through to Mackay and the highway and on to Cairns.

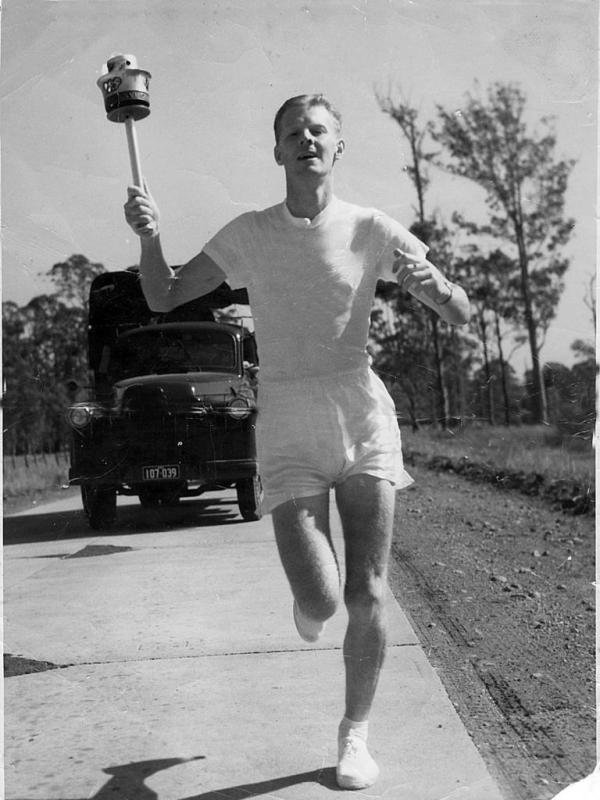

Once the actual Relay began, the Torch was carried all the way south on foot, regardless of weather or time of day or night. Runners were dropped off at marker pegs a mile apart. When they’d run their section they would pass the torch in to the support truck and be tossed a commemorative medal before the truck disappeared on its way.

At the Burdekin River, the road crossing was flooded, and once again the Torch and the convoy crossed by train. From Mackay to Rockhampton, coming south, the Relay followed the inland route and wisely avoided the St Lawrence road.

Bringing the torch through was not easy, all the same. It was dark and raining. Each young runner in his white uniform would wait nervously by his marker for the previous runner to emerge from the gloom, torch in hand, to pass on the flame – relieved when at last the lights of the support trucks showed through the dark.

The torch weighed one point eight kilograms, and after a mile held at arm’s length it weighed heavily; and the runners found that if they held it too close to their bodies, sparks blew in their faces.

People came out with hot soup down that dark, muddy road and cheered the Relay on. Souvenir hunters followed after the support trucks, illegally pulling up the markers. There must still be relay markers in sheds and cupboards all down the coast. Family members clearing out Dad’s or Granddad’s bits and pieces may puzzle over what they could be.

Rutted, muddy roads, encounters with snakes and dogs, rainy nights, leeches, mosquitoes: those Melbourne University students went home with enough stories of the wild north to create legends in the south.

Thirteen days after leaving Cairns, right on time, the Torch arrived at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the Olympic Stadium, and the Cauldron was lit.

On Friday, with the whole world watching, the 2024 Olympic Torch was carried over the iconic rooftops of Paris, and the Cauldron was lit under a magnificent hydrogen balloon that carried it off into the night sky.

In 2032, Brisbane will be hosting the Olympic Games. I’ll be interested in how that Torch Relay is run. And I might want to tell this story again.

Main photo: Don Craig, running with the 1956 Olympic Flame. cairnspost.com.au