Maryborough is the place people drive through on the way to the tourist and retirement town of Hervey Bay; but there’s much more to it than that. Maryborough is one of Queensland’s most interesting towns.

The CBD contains a collection of wonderful historical buildings: hotels, banks, and the Customs House and Bond Stores that attest to the old colonial town’s importance as a port.

Maryborough’s engineering history, too, is fascinating: its metal casting, ship-building and vast railway workshops.

Not much can be seen of all this now. Of the once huge Maryborough Flour Mill, which in 1892 is said to have been capable of producing 75 tonnes of flour a week, only the 1915 gateway arch survives.

Ship-building yards and foundries sit derelict.

Walkers Ltd Engineering, founded in Maryborough in 1867, was one of Queensland’s greatest and most dynamic companies. In its time it built trains and sugar mill machinery. It built barges, navy patrol boats and landing craft before the shipyard closed in 1974.

In 1873 the company also built what is claimed to be Queensland’s first locally manufactured locomotive, the tiny “Mary Ann”. If you’re in Maryborough on the first Sunday morning of the month you can see a replica of Mary Ann in action, buy a ticket from enthusiastic volunteers and take a ride behind her, puffing along the riverside and through the park.

In 1896 Walkers began building locomotives in earnest, over time constructing over 500 steam locomotives, 230 diesel and electric locomotives and many carriages. The company continued in engineering manufacture for well over 100 years.

The vast railway workshops near the CBD have in recent years been employed in servicing and refurbishing Brisbane’s suburban trains; even after 2022 when the Mary River flooded the town and the works.

Queensland’s regional cities are all built on rivers that flood. The Mary River is no exception, with its sources in the rain-filled hills of the Sunshine Coast hinterland, 290 kilometres to the south.

In January 2022, with a flood looming, the town built a temporary levee to protect the CBD. The levee failed when water came up the stormwater drains. Late in February, the river flooded again, and this time it worked, although many homes and businesses outside the levee were inundated with stinking water and mud.

The Mary River has flooded the town many times, most recently in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2022. The Woolworths Supermarket on the edge of the CBD was flooded twice in early 2013, and after the 2022 floods the shop remained closed for ten months. Images of the 2022 flood can been seen on Flickr:

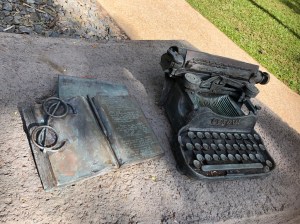

Maryborough takes its history seriously, and not just as the birthplace of P.L. Travers, author of Mary Poppins; although even Walk/Don’t walk signs in the CBD show her famous creation.

The citiy’s many museums and fine old buildings also attract visitors, and so do its war memorials.

Most spectacular is the $5 million Gallipoli to Armistice Memorial. Completed in 2018, it includes hardwood replica boats, filled with red flowers, drawn up along a supposed shoreline. A life-sized bronze statue walks ahead: Lieutenant Duncan Chapman, a Maryborough man named as the first Australian ashore at Gallipoli.

A garden walkway crosses the top of the park along Sussex Street, with sculptures, inscriptions and audios taken from the letters home of local servicemen.

Beyond this modern memorial is a massive granite column surmounted by a marble Winged Victory, erected in the 1920s to honour local men who served and died in World War One. It’s always sad to see these old “Great War” memorials, knowing that another terrible war was on its way. And many more after that.

In other parts of the world, spectacular memorials commemorate the courage and suffering of people defending their country against invaders, such as the famous London statue of Queen Boudica, who led an uprising against the conquering Romans. Her land was taken, the people enslaved. Boudica was flogged and her daughters were raped.

On Mount Zalongo in north-western Greece stands a massive monument of a row of dancing women. These were the women of Souli, who famously danced themselves and their children off the edge of a cliff to their death, rather than face capture and humiliation by invading Ottoman troops.

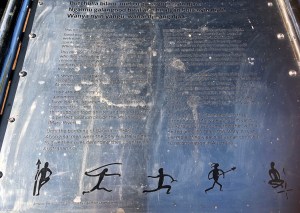

Indigenous Australians have no tradition of monumental sculptures. There are few public memorials to their resistance to invasion and the loss of their country; but in Queens’s Park, Maryborough, is a depiction in bronze of bare footprints, scattered leaves and bullet-pierced wooden shields.

The message on the accompanying plaque begins with a greeting in the local Butchulla language, and continues with a plea for respect for all those who fought and died for their country.

“Butchullam bilam, midiru galangoor nyindjaa

Ngalmu galangood biral and biralgan bula nyin diali!

Wanya nyin yangu. wanai Djinang djaa

This memorial is dedicated to Butchulla men who died defending Butchulla Country. It remembers those who gave their lives in conflicts caused by colonisation of this country from 1788.

It serves not to attach blame or guilt, but to recognise what took place and honour those Aboriginal men who lost their lives.

Pause for a moment and picture what this area may have looked like when Butchulla ancestors occupied this land – a perfect location beside the Moonaboola (Mary River).

Until the bombing of Darwin in 1942, Aboriginal men were the only Australian men to give their lives defending their country on Australian soil.

As you stand here today, please reflect on the sacrifice of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in defending this Country. We don’t know all their names, or where or when they died, but we are certain Butchulla warriors put up a fight in defence of their beloved Country. Those who gave their lives will never be forgotten.” (Abridged.)

History records that many Butchulla people died in the Wide Bay Area and on K’gari Fraser Island, both defending their homeland and in the massacres that took place quite openly from the 1840s onwards.

From the 1860s, Maryborough was one of Australia’s busiest immigration ports, and wool sugar and gold were shipped out from its wharves. It was also an entry port for Pacific Islanders brought, in the evil practice known as “black-birding”, to cut cane: work considered too hard for white people. Once Federation came, with the White Australia Policy, most of the Islanders were deported.

The early wealth of Maryborough shows in its many spectacular old houses. Some of them still show a detail that I’ve only seen here: the front of a timber house is painted, plus a metre or so along the sides, and the rest is left brown – oiled or treated another way. Evidently paint was an expensive commodity when they were built.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, manufacturing jobs in Maryborough have fallen in recent years, while the greatest increase in employment is in the service industries: health care and social assistance, retail jobs and education.

However, the Qld government has announced an initiative that it is claimed will bring 800 full-time manufacturing and other jobs to the region. Once again, Maryborough will be building trains. A massive investment of funds will see 65 six-carriage trains built in a new factory being constructed at Torbanlea, 25 kilometres northwest of town.

It’s good to acknowledge history, but when it comes down to it, what any town needs most is jobs.

I need to go back to Maryborough, and soon, because I forgot to go to the toilet. The Cistern Chapel, that is. The fabulously decorated public toilets attached to the Town Hall. Can’t miss that.