I’m always intrigued by place names and how they came about. Queensland places have had their names and their stories for tens of thousands of years; but when Europeans arrived, they knew nothing of ancient local cultures. For their maps and charts, they named places after important people and sponsors of their voyages, or their friends; their hometowns; dangers, accidents and incidents; places of home.

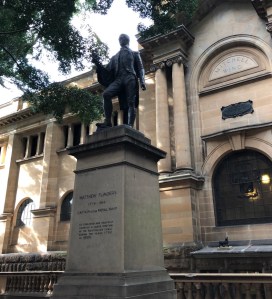

James Cook was the first to sail up the east coast. Among many other places, he named Queensland’s Glasshouse Mountains.

Matthew Flinders was next. He named Skirmish Point, at the southern tip of Bribie Island, because it was here after some trading of articles that the locals, laughing, tried to steal his hat, then threw a spear when the visitors were rowing away. That’s when the muskets came out, and locals were wounded.

Flinders, on his extended mapping voyages along the coasts of Australia, had several positive encounters with locals, but when it came to a disagreement, conflicts were decided in the usual British military way, with guns; and that is what happened at Skirmish Point.

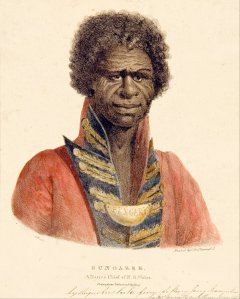

Bungaree, or Bongaree, after whom a suburb of Bribie Island is named, was a member of the Garigal clan of the Broken Bay people from north of Sydney, and he was recruited by Flinders for the voyage in the Norfolk, as well as the later Investigator voyage and others. Bungaree was respected as a person, and as an interpreter and diplomat, making positive contact with local people even though they mostly spoke different languages. Often, these were the first encounters between Europeans and Indigenous Australians.

This has been a Flinders year for me. In May, I visited the charming holiday town of Victor Harbor, in South Australia.

Victor Harbor sits on the shore of Encounter Bay, named by Flinders, near where in April 1802, as commander of HMS Investigator, Flinders met up with the French scientific and mapping expedition under Nicholas Baudin, commanding Le Géographe and Naturaliste.

The Investigator expedition, under Flinders, had been mounted by the British government for the “complete examination and survey” of the coast of New Holland, mainly to make sure the French didn’t lay claim to it, so this meeting was a tricky one, although friendly.

The National Trust Museum at Victor Harbor tells the story.

Flinders had already mapped the southern coast, across the Great Australian Bight, past Kangaroo Island and Port Lincoln and many other points all named by him. He had climbed a mountain in what were later named the Flinders Ranges. Australia itself was named by Matthew Flinders, and it’s said that his map of the continent was still being used until the mid-twentieth century.

During the arduous voyage in the leaky, unfit Investigator, ultimately circumnavigating Australia, Flinders named places in what would become Queensland. He named Bowen, and in exploring the Gulf of Carpentaria, named Mornington, Bentink and Sweers Islands.

It was Flinders who named the Great Barrier Reef(s).

In 1799, three years earlier, Flinders had been commissioned to sail north from Sydney looking for rivers – potential harbours and ways to reach the unknown inland. Sailing through Moreton Bay in the tiny HMS Norfolk, he mapped and named several Moreton Bay islands and Red Cliff Point.

The mangroves and sandbars of Moreton Bay hid from him the Logan, Brisbane and Pine Rivers, but he gave Pumicestone Passage its name, calling it, hopefully, Pumicestone River.

Anchored off the southern end of Bribie, Flinders went seeking a lookout point, heading for the nearby Glasshouse Mountains.

From near today’s Donnybrook, with Bungaree and two seamen, Flinders reached Beerburrum and climbed it. Tibrogargan, a little to the north, was too difficult, and the group camped nearby beside Tibrogargan Creek.

There is now a cairn commemorating the expedition in the Matthew Flinders Park Rest Area near their campsite.

In August 1803, Flinders left Sydney for England in the Porpoise, to arrange a better ship for survey work. 450 kilometres off Keppel Bay (Emu Park) the Porpoise and companion ship the Cato were wrecked on the reef still known as Wreck Reef. The survivors were marooned on a sandbank, including Flinders and his cat.

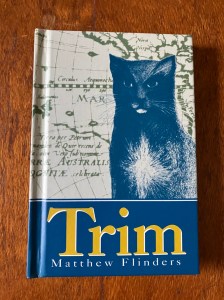

Trim, the cat, had been born on HMS Reliance in 1799, during its voyage to Sydney with Flinders as master’s mate. Trim and Flinders were companions during their voyages on the Norfolk, the Investigator, the Porpoise and the Cumberland. Wherever you find a statue of Matthew Flinders, his cat will be with him.

Flinders wrote charmingly about Trim, his account published in the little volume “Trim”, which I bought at Bribie Island Seaside Museum.

Stuck on a sandbank and expecting no rescue, Flinders with a crew of thirteen set off in a cutter to row and sail the 1100 kilometres back to Sydney for help. In less than two weeks they arrived there, and headed back in the small, barely seaworthy Cumberland, with two other ships, to rescue the stranded men, and the cat, from the sandbank.

Determined to get back to England and arrange his ongoing explorations, after the rescue of the marooned crew, most of whom returned to Sydney, Flinders headed north and west in the Cumberland, eventually landing for repairs at the French colony of Mauritius, not knowing that the French-British wars had broken out again. He was taken prisoner, and spent six and a half miserable years there before being allowed to return home.

It was on Mauritius that Trim was lost.

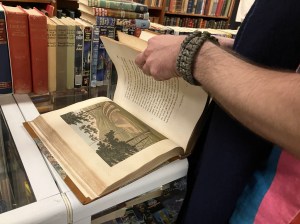

This long imprisonment contributed to Matthew Flinders’ death at the age of forty, in July 1814. “A Voyage to Terra Australis” the book that summarised his life’s work, was published the day before he died.

In the splendid O’Connell’s Bookshop in Adelaide I got to see a valuable copy of this work, the result of so much adventure, pain and determination.

Matthew Flinders was buried in a London church graveyard, but the site was redeveloped in later years and his grave was lost. In 2019, archaeologists undertook a survey of the old graveyard, near Euston Station, prior to construction of a new branch of the London Underground, and found the lead breastplate which marked his grave.

It was exciting news. The “Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home” group began to work towards his reburial in his hometown of Donington, Lincolnshire.

In July 2024, 210 years after his death and with full military honours, Matthew Flinders was laid to rest in the Church of St Mary of the Holy Rood, Donington. As well as descendants of the Flinders family, two descendants of Bungaree were at the ceremony.

The name of Flinders now appears all over Australia, including on major streets in both Melbourne and Townsville, and on Flinders Parade, Sandgate, where my great-grandparents lived a hundred years after the little Norfolk sailed by on its way up the bay.

I’ve walked the track to the top of Beerburrum, and climbed Tibrogargan (the western, easier side); and I’ve also been to the top of a peak which can be seen to the south-west from many of Brisbane’s high points: Flinders Peak. It was a scramble in places, but worth it for the view.

In 1799 Flinders spotted the peak from the sea and named it “High Peak”. When John Oxley sailed this way twenty-five years later, searching for a suitable place to build the convict settlement that would later become Brisbane, he renamed it Flinders Peak.

Of course, like all of these places, it already had a name: Booroong’pah. Like all of these places, it already had its own long-established stories.

The Matthew Flinders story is just another story of Australia, and of Queensland; but it will always be a story both inspirational and moving.

About Matthew Flinders

- “Flinders: The life, loves and voyages of the man who put Australia on the map”, Grantlee Kieza, 2023. Excellent biography, based on primary sources

- “My Love Must Wait”, Ernestine Hill, 1941, my first introduction to the story Of Matthew Flinders

- “A Biographical Tribute to the Memory of Trim”, Matthew Flinders, published 1977, from the archives of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

- “In the Footsteps of Flinders: Memorial to great navigator unveiled,” article by Clem Lack for Royal Historical Society of Queensland, 1963, describing Flinders’ expedition to Beerburrum.

- “Matthew Flinders’ Cat”, Bryce Courtney, 2002. A novel of Sydney, with Trim’s story vividly told.

Main picture: Portrait of Captain Matthew Flinders, RN, 1774-1814. Toussaint Antoine de Chazal de Chamerel. 1806-07, Mauritius Art Gallery of South Australia