Floods.

I’ve written many stories about many parts of Queensland on this blog, and so many of them describe floods.

Maryborough, Ipswich, Rockhampton. https://roseobrienwriter.blog/2024/02/06/maryborough/

Townsville, Bundaberg, Ingham, Charleville. https://roseobrienwriter.blog/2021/07/24/road-trip-to-ingham/

The Brisbane, Bremer, Mary, Burdekin and Flinders Rivers. https://roseobrienwriter.blog/2020/12/12/syphoning-petrol/

The Gulf Country, the Horror Stretch and the Cassowary Coast. https://roseobrienwriter.blog/2018/11/08/horror-stretch/

These are places I know well, and I feel for the people who live and work there; especially in the north. People wading through the ruins of their flood-damaged homes; cane, banana and beef farmers coping with the ruination of their hard-won livelihoods.

I remember the cattle farmers of the Flinders River catchment who, during the 2019 floods waited helplessly for the waters to go down as helicopters brought back images of mobs of cattle, including precious breeding herds and cows with calves, dead of cold and hunger, crowded against fences and on small patches of higher ground. It is estimated that 500,000 head of stock died in that flood.

And now floods have happened again – are still happening – in tropical Queensland. The State premier, an Ingham native, holds a press conference describing the community’s sorry situation: highway cut both north and south, houses flooded, no electricity, a breakdown in the water supply, supermarkets empty, and two lives lost. Further north, in and around Cardwell, houses flooded that have never been flooded before.

The Herbert River catchment of 9000 square kilometres has its headwaters in the Great Dividing Range near Herberton, and it collects a lot of tropical rain before it makes its way down to the flat canefields around Ingham. The Cardwell Range is steep and high and close to the town, so the catchment there is not nearly as big. But what is going to happen, when almost two metres of rain falls in three days?

The Burdekin River catchment of over 130,000 square kilometres is the size of England and stretches from north of Charters Towers and Greenvale to south of Alpha. Charters Towers has been flooding all week, and that water is heading for Ayr and Home Hill on the coast.

Sugarcane can be laid low by a flood, and recover, if the water doesn’t lie there too long. On the rich flood plains around Ingham, water has been lying for days, and still it rains.

An agriculturist, an expert in banana growing, told me that in the case of a cyclone, if a farmer lops the plants back they will survive and regrow. How would you go about that? It would take days, and a huge amount of work, and even with excellent modern forecasting, satellites and radar, cyclones are unpredictable. They can veer south or north or move back out to sea.

More heavy rain is forecast across North Queensland. The water will run to the coastal towns and farms and also to the vast plains of the inland, where rivers like the Flinders will break their banks and spread across the land, cutting the few sealed roads and the one railway line that runs east-west across the State.

In Queensland, rich in resources though it is – agriculture and mining in particular – we don’t have many people. The US state of Texas, iconic to Americans for its size, has an area of 697,000 square kilometres, compared to Queensland’s over 1,700,000 square kilometres. However, Texas has a population over five times the size of Queensland’s. That makes a huge difference when it comes to tax base and industry. It seems we don’t have the population, or the votes, to create better, more resilient transport infrastructure.

We also have a more extreme climate than Texas, especially when it comes to floods. Tornados are deadly, but they move quickly across the land. Rain depressions hang around.

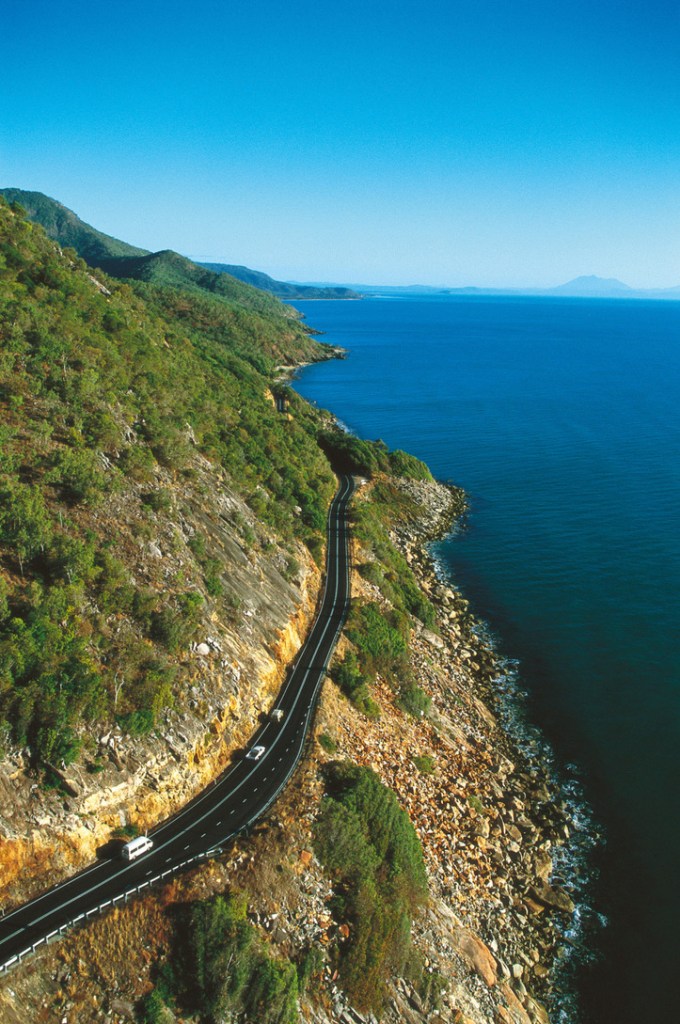

Queensland has only one highway and one railway going along the coast, and because of shortage of population and extremes of climate, there are almost no entirely sealed roads west of the ranges linking north and south.

During this month’s major flood event in North Queensland, the one main railway line was soon cut in several places. https://www.railexpress.com.au/rail-bridges-submerged-as-floods-batter-north-queensland/

When the Bruce Highway bridge at Ollera Creek was washed away over the weekend, north of Townsville, Far North Queensland was cut off from the world except by air and sea.

Trucks carrying supplies to the Far North and people trying to return home faced an extra 1200 kilometres’ journey, travelling by western Queensland sealed roads, to reach Cairns. And these roads are under threat of closure at any time. Many are stranded. https://qldtraffic.qld.gov.au/

If the continuing flood rain results in damage to the railway and highway linking Townsville and Mount Isa, as happens all too often, transport and supply of essential goods may be affected for weeks.

For all sorts of reasons, including strategic concerns, the continuing and increasing vulnerability of Queensland’s transport routes is a major threat to our way of life and security.

People who live and work in the north and west of the State feel bitter that regions that produce so much of Queensland’s wealth continue to be so vulnerable to the weather. And as climate change deepens, it will only get worse.

It’s a worry.

In the southern states and Canberra, people have always regarded Queensland with a kind of affection as a weird, distant place, a place of extreme weather, crocodiles, bogans and dodgy politicians. Greater Brisbane makes up half the population of the State, and a lot of Brisbane people seem to be largely ignorant of regional areas. To them, north means Noosa, and west means Toowoomba.

So where is the will to sink vast sums into flood-proofing North Queensland for the future? Bipartisanship in politics would be a start.

I’m tired of writing about floods.

Main picture: Maryborough flooded at Sunset. 2022 Qld Reconstruction Authority